Sculptures by François du Plessis

Is François du Plessis a bibliophile? This question may astonish, as for many years books and also magazines have been the basic material for his artistic work. Yet the question stands: is François du Plessis a bibliophile? – Ultimately, we will pose this question once more and then, hopefully, will be able to answer it.

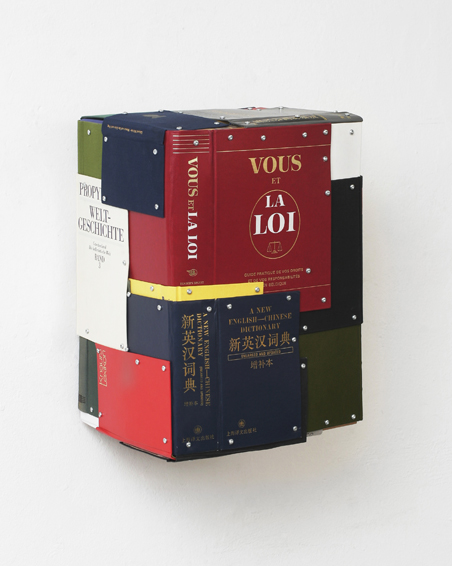

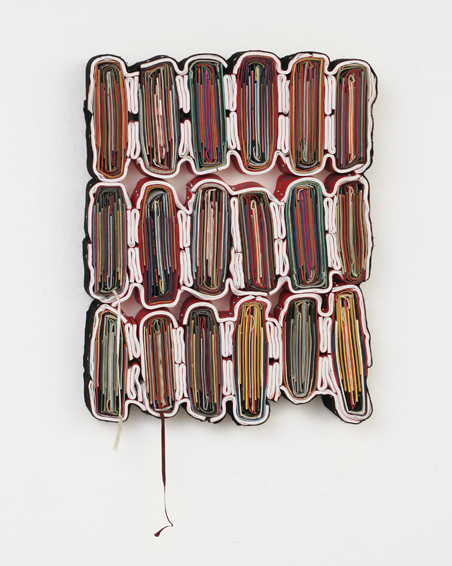

François du Plessis’ dealing with the book is not altogether innocuous. It is rather in a very solid, almost abstract way physical and tangible. His objects deal with nothing less than the realisation of new forms, not the replication of a text, not the illustration of a thought contained therein, they are about sculptures, about a three-dimensional picture. Thus come into being erratic, frayed, earlier on whitened, but today often untouched reliefs, round images, cubes, small wild book creatures or towering winding steles. They cannot be counted among the so-called artist books. Those painters’ books, scribbling pads and virtuous designs which are published, either in the well-maintained enclosures of the bright publishing culture or the shadowy recesses of self-publishing.

These works tell us that their creative process of has absolutely nothing in common with the politicizing, condensed apotheosis which wafts around those on which the Zeitgeist feeds; illustrate great ideas or at times authoritarian demeanour, even resistance, and of which Biermann only has to say that they are ‘dissident trophies’ (i).

For the reality of these object, their essence, the contents of the books used is not important. Not the thought, not the word are the material here, as it was true for the thought-gathering Heiner Müller, but the paper, the bound volume of perhaps a few hundred pages; important is the substance, the materiality (in the physical sense), that carries the text and how it relates to potencies and colours.

For his book objects, François du Plessis disassembles the original books. For him, their worth is not hidden behind the closed covers. Binding and pages, the body, that is the material to be reassembled and held together by screws to re-emerge as a gigantic reminiscence of a tree grate, as a speaking (sic!) Tower of Babel or, recently, as a cunning book reptile. The prevailing forces are enormous.

Where screws penetrate binding and paper, there everything is tight, remains no gap. In other places, however, abysses yawn and passages lead into small spaces, offering a view of the past, of letter sequences, and punctuation marks, and cover colours. The dark spots lend structure to the body, shadows emerge. The object begins to stir optically. It seems to be alive. These impenetrable layers and random structure distortions are the more important as they lead the observer further away from the source, the book. It is because of them that the source material will turn into a totally new, independent, associative work of art.

Thus sculptures come into being. Distinct, unique figures, solid, sensuous, playful, never didactic but always new, always surprisingly different. br> Let’s come back to our question asked at the beginning: is François du Plessis a bibliophile? Yes, I think he is. For ‘bibliophile is admittedly the love for books, but not necessary for their content’ (ii). After all, these book objects tell their own story – book stories does not mean the stories in the book, but those which tell what has become of these books. Fascinating new material beings.

Stefan Skowron

Aachen, im April 2011

i. Wolf Biermann, Ein öffentliches Geschwür, in: DER SPIEGEL 3/1992, 13.01.1992.

ii. Umberto Eco, Die Kunst des Bücherliebens, Carl Hanser Verlag München 2009, S. 32.